The Path into Studying Jazz

The Path into a Jazz Degree

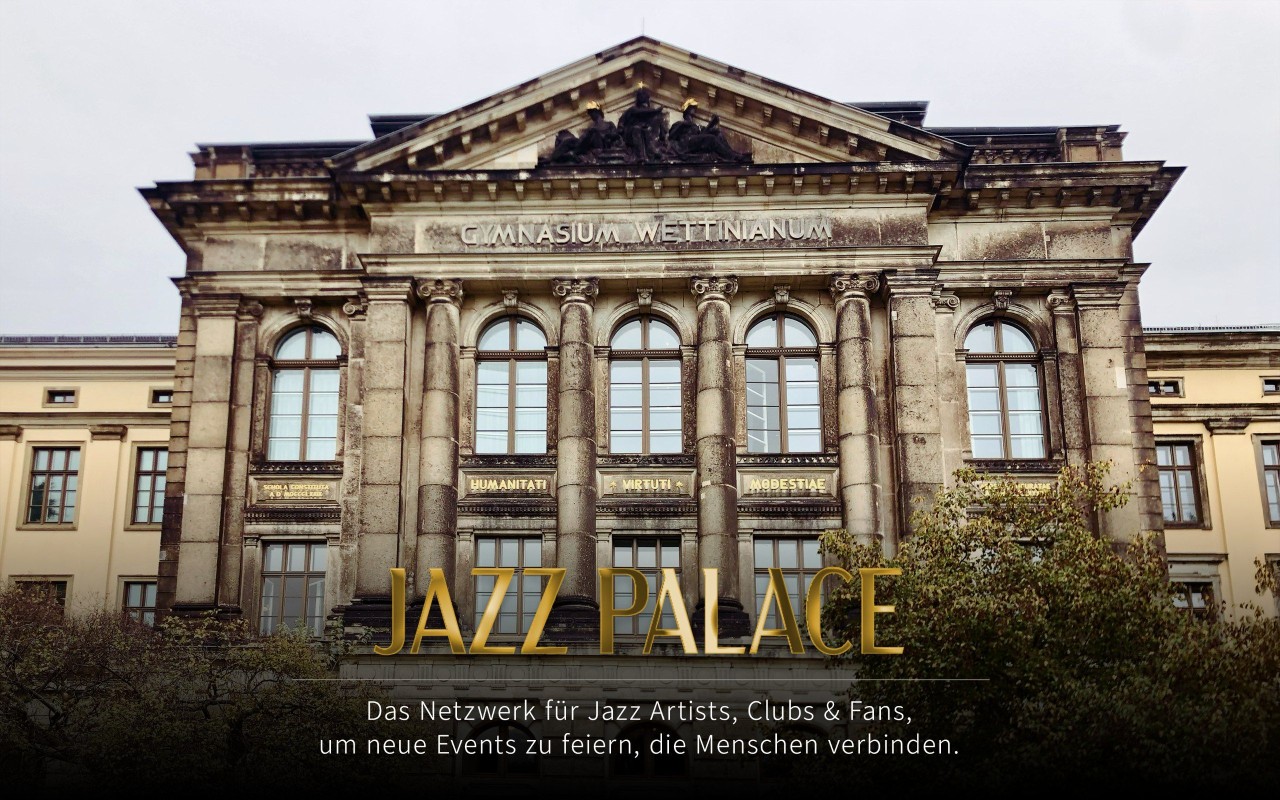

I’m Elina, and I’ve just recently joined Jazz Palace. I’ll be responsible for many parts of the editorial work, and I’m excited that we’re creating a space where we can exchange ideas and connect with one another.

There will be regular articles and features—and I’d like to begin by giving a small insight into what it’s actually like to study vocal performance and what the path there can look like.

I’m 22 years old. I started playing classical piano at the age of five, and singing followed when I was 15. My family is very musical, and at home I was encouraged in my creative processes from an early age—so the idea of turning them into a profession never felt unrealistic. Alongside singing came songwriting, and my own music was at the center from the very beginning. Quite quickly, I began performing—for example in a jazz big band or with my first own band. Still, it took me some time to say about myself: I am already a musician.

But for me, that realization was necessary in order to fully commit to the path ahead and find the courage to professionalize the music I love so deeply. From that point on, things moved relatively fast: the decision to study, to put everything on one card, to move to a new city, and to dedicate the coming years to learning.

I completed two years of a pre-college music program (Studienvorbereitende Ausbildung, or StuVo) in Leipzig and auditioned this year at five universities for Jazz/Rock/Pop vocal studies. Now I’ll begin my studies in Dresden. At first, I had no idea that pursuing what I love would require such an intense journey.

To study music, art, or acting, you need more than a strong high school diploma. It requires years of artistic preparation, financial resources, a portion of luck—and definitely perseverance to get through the marathon of entrance exams.

In Germany, around 18 public universities offer jazz vocal programs, and on average only one to five spots are awarded per application cycle. To even be invited to the entrance exams, applicants usually go through a video pre-selection round and, if successful, receive an invitation to the live auditions. These may take place over several days or be condensed into one very long examination day.

The exams typically include music theory, ear training, piano as a secondary instrument, and the main subject—vocals. Passing without prior musical training is possible, but it’s a much longer road—often requiring additional years of applications—compared to those who attended a specialized music high school or had private lessons from an early age.

For almost everyone, however, a pre-college program (StuVo) makes sense in order to meet the specific requirements of the universities. These programs are offered by music schools in many larger cities—Berlin or Leipzig, for example—and usually last one to two years of intensive study. Even for StuVo, there is an entrance exam, because the teachers want to know whom they can train within one or two years to realistically have a chance at passing university auditions.

For vocal studies, I would say the essentials are: a good ear (intonation), a sense of rhythm, a healthy and trainable voice, and at least a basic understanding of jazz. That means applicants should have sung a jazz standard before, improvised, and be able to interact with a band and count them in during the exam.

Once admitted to StuVo, students receive extensive lessons from established jazz and pop musicians. In Leipzig, for example, the curriculum includes ensemble classes, listening and jazz history, vocal ensemble, rhythm training, theory, and ear training. I often heard people say that StuVo already feels like its own full education—only without an official degree, but ideally with a ticket into university.

My personal StuVo time was marked by inspiring input and close collaboration. The teachers at the Neue Musikschule in Leipzig take their teaching assignments very seriously and guide you carefully through the preparation and examination process. As exciting as it is to travel to at least five different cities, to stand in front of unfamiliar examiners, and to have 15–20 minutes under pressure to present your prepared program and demonstrate everything you’ve learned—it’s just as important to have a strong backbone and people around you who know from experience exactly what that feels like.

I would say that when you begin your studies, you are already a musician—you don’t become one there. The degree then gives you form, a toolbox to professionalize your voice and musical knowledge, to develop your artistic identity, and to figure out how you want to position yourself in professional life.

University acceptances are announced at different times. Sometimes you know the same day that it didn’t work out—or the professors are so enthusiastic that they offer a spot during the audition or call personally the next day. In most cases, however, you wait about two weeks for the results. Some applicants are placed on a waiting list and may, with a bit of luck, receive a spot later. It’s an emotional rollercoaster, as the conditions can sometimes feel arbitrary. It even happens that someone passes everything with top marks but cannot be offered a place because there simply isn’t enough capacity.

From my StuVo cohort, we’re now starting our studies in various cities—Leipzig, Bern, Nuremberg, Weimar… and Dresden. The application months from January to June were a huge challenge, and I believe we all reached our limits at times.

And yet, these shared experiences brought us very close together—and in the end, we all made it. Now we’re beginning our jazz studies and will be able to share our perspectives and support one another from different cities (and even countries).

I’m looking ahead to my studies with great excitement and curiosity, and I can’t wait to see what lies ahead for us.